This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered twice a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Welcome back.

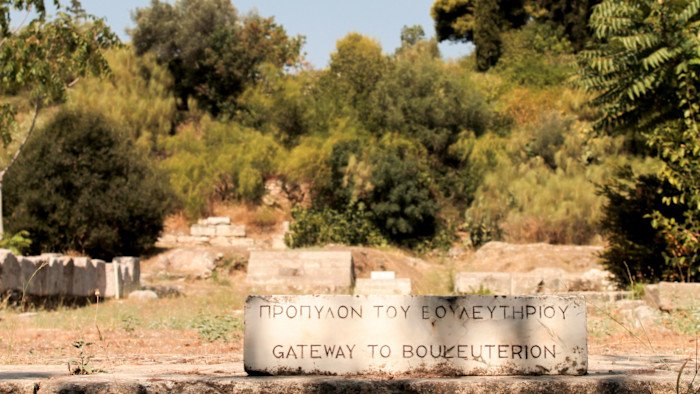

Fund managers have a duty to act in the best interest of their clients. But who gets to decide what that means? And does BlackRock have anything to learn from ancient Athens?

Have a great weekend.

GOVERNANCE

The case for investor assemblies

True democracy, Aristotle reckoned, was built not on mass elections but on klerosis: randomly chosen groups of citizens making judgments on behalf of their peers.

Could that notion catch on in the modern financial sector?

Consider an unusual recent episode from the Netherlands, described in a journal paper published last week. Pensioenfonds Detailhandel — a pension scheme managing €30bn ($35bn) for retail sector workers — had been allocating 1 per cent of its assets to private-market investments aimed at social or environmental impact. But was this what its members wanted?

The fund teamed up with a group of academics in an effort to find out, through a two-stage process. They collected 49 pension scheme beneficiaries, randomly selected but reflecting the demographic mix of the 1.2mn-strong membership. The group gathered for three days, during which they were given briefings on impact investment by a range of speakers.

It was stressed to them that such investment came with the potential for lower returns, “so as not to give people the idea that there is a free lunch”, study co-author Paul Smeets, of the University of Amsterdam, told me.

Most of the participants nonetheless said they wanted a significant expansion of impact investing — a suggestion on which the board agreed to consult the wider membership. In this second stage, a sample of 220,000 scheme beneficiaries were asked to choose between three options for its impact investing strategy, with the board committing to implement whichever was most popular.

That proved to be the option of increasing the fund’s impact allocation to between 2 and 5 per cent of the portfolio, which got 41.5 per cent of votes. (A further 31.3 per cent voted to keep the allocation at 1 per cent, while 13.2 per cent voted to drop impact investing altogether; the rest picked “don’t know”.) The fund is now moving to implement the promised expansion.

The exercise will bolster the “legitimacy” of the fund’s impact investment strategy, which will better reflect the wishes of its members, said Pensioenfonds Detailhandel responsible investment manager Louise Kranenburg.

The Dutch fund’s approach may look risky to some of its peers. At the start of the three-day group meeting, nearly half the participants rated their financial literacy at the bottom of the scale. It would be in their best interest, some would argue, to leave investment decisions to the professionals. And any fund that’s not acting in its beneficiaries’ best interest will quickly run into very ugly legal territory around fiduciary duty.

The architects of this exercise contend that the questions at issue here are not technical ones requiring specialist knowledge, but rather a matter of taking into account savers’ existing ethical positions. Many pension scheme boards have assumed that “on moral issues, they know what [their clients] need”, said Maastricht University’s Rob Bauer, who led the study. “I think that’s a fundamental mistake.”

The dominant three US asset managers should also consider adopting a similar approach as they grapple with public and political scrutiny over their use of shareholder votes at the companies they invest in, according to a paper last year by Nobel-winning economist Oliver Hart of Harvard University, Yale’s Hélène Landemore and Luigi Zingales of the University of Chicago.

BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street have started rolling out systems that enable retail investors in their funds to choose between several voting policies, each with a different approach to environmental, social and governance issues. But these options have enjoyed limited uptake due to “rational apathy”: each small investor knows that their voting preferences will have a negligible impact on the outcome of any shareholder meeting.

Instead, Hart and his co-authors wrote, the big asset managers should allow their approach to votes on “value vs values trade-offs” to be steered by a body of about 150 investors drawn by lot.

“We believe investor assemblies are a more legitimate way to make the inevitably political and moral decisions that are currently made by managers in investment funds,” they wrote.

“Investor assemblies would . . . not be asked to calculate the optimal hedging strategy against interest rate risk,” they continued. “Instead, they would be asked whether they are willing to accept a slightly lower return in order to treat slaughtered animals in a more humane way. This decision is not a technical decision; it is a value-values decision.”

So far, the asset management giants have shown no public interest in the investor assembly concept. It has, however, got the attention of UK workplace pension scheme Nest, which manages £55bn ($74bn) for more than 13mn members. Last week, Nest announced its first assembly of members “to discuss and make recommendations on key issues affecting their pensions”.

The exercise will be run in partnership with Cranfield University’s Emmeline Cooper, who also worked on the Dutch one mentioned above. “Ordinary pension beneficiaries and savers are quite capable of making quite sophisticated recommendations to their pension scheme boards on how they’d like to invest their money,” Cooper told me. “It’s a very simple point but one that’s widely ignored, or not believed, across the financial sector.”

Smart reads

-

The International Energy Agency’s ministerial meeting ended without a joint statement, a break from the norm of recent years. The outcome reflected disagreement between US energy secretary Chris Wright and his European counterparts on the importance of clean energy expansion.

-

Power-hungry AI could drive large-scale energy poverty without increased investment in renewables, argues Chinese wind power tycoon Zhang Lei.

-

In a US disability discrimination lawsuit, a US court will need to decide: how much sleep does a banker need?