The evaluation of energy performance of water companies involves estimating two crucial synthetic indicators, EE and EP, utilizing the StoNED method developed by Kuosmanen and Kortelainen21. This method represents a synthesis of non-parametric (linear programming) and parametric (econometric) approaches. It uniquely incorporates a stochastic noise term into a non-parametric DEA-style efficiency frontier, which accounts for both inefficiency and stochastic noise, aligning it with parametric frameworks22. StoNED, like DEA, operates without assumptions regarding the production function’s functional form, maintaining critical properties such as convexity, monotonicity, and returns to scale, as established in the DEA methodology23. A significant advantage of the StoNED method over traditional DEA is its capacity to handle heterogeneity among water companies by including environmental variables24.

The process of evaluating energy performance using StoNED begins with the estimation of EE scores, followed by the determination of EP scores. Each stage involves specific procedures which are described as follows.

Energy efficiency estimation

The estimation of the EE for each water company involves several stages, described as follows:

Stage 1. Definition and estimation of the energy frontier function:

The energy frontier function relates the energy consumption of the assessed water companies with their outputs (volume of drinking water and number of water connected properties) along with other environmental variables:

$${{EN}}_{i,t}=f\left({y}_{i,t},{z}_{i,t}\right)+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}$$

(1)

where f represents function, EN is the energy consumption, i represents the water company at any time t, y represents a set of outputs produced by water companies and, z is a set of environmental variables that could influence the energy consumption of the water services. Finally, the term εi,t is the composite error term of the frontier model. It consists of two components, inefficiency, ui,t, and noise, vi,t. Inefficiency follows the normal distribution and noise follows the standard normal distribution21. In other words, \({\nu }_{i,t} \sim N\left(0,{\sigma }_{\nu }^{2}\right)\) and \({u}_{i,t} \sim {N}^{+}\left(0,{\sigma }_{u}^{2}\right)\), where \({\sigma }_{v}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{u}^{2}\) are the variance of noise and inefficiency, respectively. The expected value of inefficiency is defined by \(E\left(u\right)=\mu\) and is directionally proportional to the parameter \({\sigma }_{u}:\mu ={\sigma }_{u}\sqrt{2/\pi }\) where σu is the standard deviation of inefficiency. Furthermore, parameters α, β and γ are recovered after the estimation of the energy frontier model in Eq. (1).

The energy function frontier is estimated by solving the following non-linear programming model using convex nonparametric least squares approach24:

$$\min \mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{I}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{t=1}^{T}{\varepsilon }_{i,t}^{2}$$

(2)

subject to:

$${{ln}{EN}}_{i,t}={ln}\left({{\alpha }_{i,t}+\beta }_{i,t}{y}_{i,t}\right)+\gamma {z}_{i,t}+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}\,i=1,..,I{{;}}\,t=1,\ldots ,T$$

$${a}_{i,t}+{\beta }_{i,t}{y}_{i,t}\ge {\alpha }_{j,w}+{\beta }_{j,w}{y}_{j,w}\,i,j=1,\ldots ,I{{;}}\,t,w=1,\ldots ,T$$

$${\beta }_{i,t}\ge 0\,i=1,..,I{\rm{;}}\,t=1,\ldots ,T$$

In Model (2), the β coefficients are interpreted as marginal products25. The constant term α captures the scale of operations of water services. In this study, it was set ai,t = 0 because water companies operate under constant returns to scale, i.e., at the most productive scale size17. The second constraint in Model (2) guarantees that the energy function is convex and the last constraint ensures monotonicity in outputs23,26.

Stage 2. Estimation of energy efficiency score for each water company

EE for each water utility at any time t is estimated based on the residuals obtained from Model (2)24. The value of energy inefficiency and the variances of inefficiency and noise are estimated based on the method of moments27,28 and imposing half normal distribution for inefficiency and standard normal for noise29:

$${EN}\left({u}_{i}{\rm{|}}{\varepsilon }_{i}\right)={\mu }_{* }+{\sigma }_{* }\left[\frac{\phi \left(-{\mu }_{* }/{\sigma }_{* }\right)}{1-\Phi \left(-{\mu }_{* }/{\sigma }_{* }\right)}\right]$$

(3)

where ϕ is the standard normal density function and Φ denotes the standard normal cumulative distribution function:

$${\mu }_{* }=-{\varepsilon }_{i}{\sigma }_{u}^{2}/\left({\sigma }_{u}^{2}+{\sigma }_{v}^{2}\right)$$

(4)

$${\sigma }_{* }^{2}={\sigma }_{u}^{2}{\sigma }_{v}^{2}/\left({\sigma }_{u}^{2}+{\sigma }_{v}^{2}\right)$$

(5)

Based on energy inefficiency estimated, \({\hat{u}}_{i},\) the EE for any water company i at any time t is derived as follows:

$${{EE}}_{i,t}=\exp (-{\hat{u}}_{i,t})$$

(6)

EEi,t ranges from zero to one. A score of one indicates that the water company is fully energy efficient, while scores below one denote energy inefficiency, highlighting the potential to reduce energy use compared to their peers without diminishing the generation of outputs.

Stage 3. Quantification of potential energy use savings

For energy inefficient water companies, potential energy use savings are estimated as follows:

$${{PEN}}_{i,t}={{EN}}_{i,t}\times \left(1-{{EE}}_{i,t}\right)$$

(7)

where ENi,t is the actual energy consumption for each water utility i at any time t, expressed in kWh/year, and EEi,t is the EE score estimated on Eq. (6).

Energy productivity estimation

EP estimation involves extending EE to a temporal setting by evaluating how water companies’ energy performance has evolved over time. The methodological approach applied consists of three stages, defined as follows:

Stage 1: Definition of the energy distance function:

The energy distance function is an input distance function, as energy is an input required to deliver water. According to Färe et al.30 an input distance function indicates the maximum reduction of inputs for a given level of outputs. Hence, the energy distance function shown in Eq. (8) measures the maximum reduction in energy use needed to produce specific outputs by water companies:

$${D}_{t}\left({x}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)=\max \left\{\xi :\left(\frac{{x}_{t}}{\xi }\right)\in {L}_{t}\left({y}_{t}\right),\xi > 0\right\}$$

(8)

where ξ shows the maximum contraction of inputs (energy), 1⁄ξ, for a given level of outputs and L(y) represents the input set, i.e., the vector of inputs employed to produce the vector of outputs31.

Stage 2. Definition of the energy productivity index (EPI) and its components

The estimation of the energy distance function (Eq. 8) for two periods, t and t + 1, allows defining an EPI, which provides information about changes in energetic performance over the periods considered:

$${{EPI}}_{t,t+1}={\left(\frac{{D}_{t}\left({x}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)}{{D}_{t}\left({x}_{t+1},{y}_{t+1}\right)}\times \frac{{D}_{t+1}\left({x}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)}{{D}_{t+1}\left({x}_{t+1},{y}_{t+1}\right)}\right)}^{1/2}$$

(9)

The EPI is decomposed into two components: EEC (Eq. 10) and ETC (Eq. 11):

$${{EEC}}_{t,t+1}=\left(\frac{{D}_{t+1}\left({x}_{t+1},{y}_{t+1}\right)}{{D}_{t}\left({x}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)}\right)$$

(10)

$${{ETC}}_{t,t+1}={\left(\frac{{D}_{t}\left({x}_{t+1},{y}_{t+1}\right)}{{D}_{t+1}\left({x}_{t+1},{y}_{t+1}\right)}\times \frac{{D}_{t}\left({x}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)}{{D}_{t+1}\left({x}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)}\right)}^{1/2}$$

(11)

EEC is known as “catch-up” as it measures the extent to which each water company has approached or moved away from the energy efficient frontier, that is, the one that determines the best performance32. On the other hand, ETC captures the existence of technical progress or regress, indicating the positive or negative shift of the energy efficient frontier33.

The interpretation of the EPIt,t+1 and its components (EECt,t+1 and ETCt,t+1) is analogous. A value greater than one indicates gains in energetic performance over the years (EPI), improvements in energy efficiency (EEC), and technical progress (ETC). Conversely, values lower than one for EPI, EEC and ETC indicate a decline in the overall energetic performance, a decrease in the energy efficiency, and technical regression, respectively.

Stage 3. Estimation of the EPI, EEC and ETC

The EPI and its components (EEC and ETC) defined in Eqs. (9–11) are estimated employing the StoNED method considering as well Eqs. (1–6)27,34,35,36:

$${{EPI}}_{t,t+1}=\exp ({Trend}+\varepsilon \left(i,t+1\right)-\varepsilon \left(i,t\right))$$

(13)

where exp (Trend) and \(\exp (\varepsilon \left(i,t+1\right)-\varepsilon \left(i,t\right))\) represent ETC and EEC, respectively. ETC is estimated though the computation of the coefficients in Model (2), whereas EEC estimation involves solving Eqs. (2–6).

Case study description

The case study focuses on the English and Welsh water industry, which was privatized in 1989 by transferring the water supply and sewerage assets, along with the relevant staff, of the ten existing regional water authorities into limited companies37. This privatization led to the establishment of two types of water companies: WaSCs and WoCs. As in most countries, English and Welsh water companies operate as monopolies; hence, regulation plays a crucial role in protecting consumers and the environment38. Specifically, water companies in England and Wales are regulated by three main bodies: the Water Services Regulation Authority (Ofwat), which is the economic regulator; the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), which is the environmental regulator; and the Drinking Water Inspectorate, which is the water quality regulator39. Three relevant functions of Ofwat are to set water tariffs for each water company every five years according to a revenue cap model, to promote economy and efficiency, and to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development37.

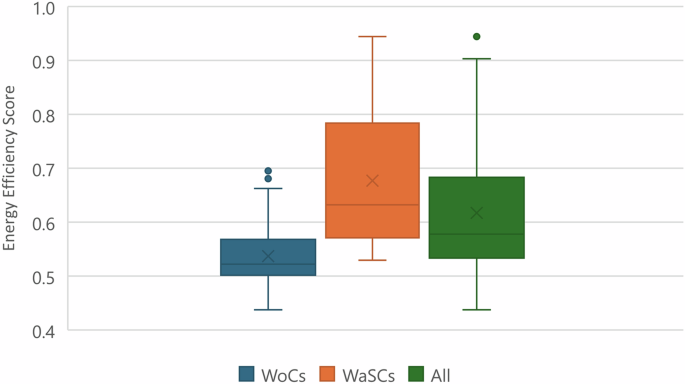

WaSCs provide both water and sanitation services, whereas WoCs provide only water services. Therefore, to compare the energetic performance of both types of water companies, the case study focuses on assessing the EE and EP in the provision of water services by both types of companies. Based on available statistical data, the evaluation period spans from 2008 to 2020, encompassing three regulatory periods. The total number of observations assessed was 228.

The selection of variables for assessing the energetic performance of water companies was based on data availability and results from previous studies40,41,42,43. The energy used for abstracting raw water from water bodies, treating it to produce drinking water, and distributing it to consumers was selected as the input. Since the study focused on drinking water services, two outputs related to the main function of water companies were considered: (i) the volume of drinking water delivered and (ii) the number of water connections. Both outputs are relevant as they are directly related to the scale at which each water company operates44. For consistency, energy used and water delivered were expressed in MWh per year and Ml per year, respectively.

Environmental variables potentially impacting the energy performance of water companies were selected using the same criteria as for selecting inputs and outputs. The main source of raw water was included in the assessment by integrating the percentage of surface water and groundwater abstracted to produce drinking water. The quality of raw water was also identified as a determinant of energy efficiency in drinking water treatment plants45. Consequently, the number of works required at treatment plants to clean water from surface and groundwater sources and the percentage of raw water necessitating high levels of treatment were incorporated into the assessment46. Finally, population density, defined as the number of people served divided by the length of water mains, was included in the assessment to account for potential economies of density in the energetic performance of water companies47.

Tables 3 and 4 present the main statistical values of the inputs and outputs (Table 3) and environmental variables (Table 4) involved in the energetic performance of water companies in England and Wales.