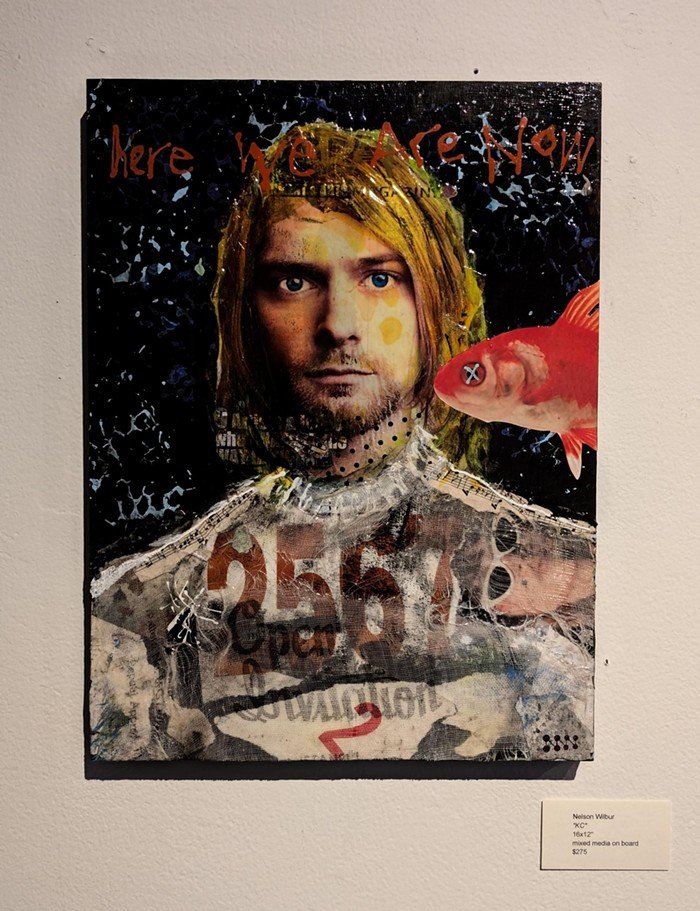

There he was again, Kurt Cobain. This time with intense (almost accusing) eyes near the top of a mixed media collage by Nelson Wilbur. It’s called “KC,” and is part of a show at Vermillion Gallery that features work by artists associated with Georgetown’s Fogue™ Studios & Gallery. I looked at “KC” for several minutes (the iconic sunglasses, strips of music notes, words from Nirvana’s biggest hit, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the mysterious number 2567), and then I spent several minutes wondering why I never fail to stop and stare at any work featuring the dead rock star. “KC” is, for sure, a fine piece of art, but if it wasn’t for its subject, I would have moved on to the next work by Wilbur. Cobain’s image always presents me with a riddle that I try to solve, and always fail to do so. Is it in his eyes? The reddish fish in “KC” is almost kissing him. Why?

Late the following day, August 11, I learned that Seattle’s eminent rock critic Charles Cross died in his sleep.

The unexpected passing of Seattle’s most prolific music journalist & historian Charles R. Cross has been weighing on my mind the past few days.

I sat down with him a few months ago at his home to talk about his career, music, and Kurt’s legacy.

RIP, Mr. Cross. I’m miss you.💙 pic.twitter.com/uMNUswIHoz

— Matt M. McKnight (@mattmillsphoto) August 14, 2024

Cross authored the definitive Cobain biography, Heavier Than Heaven, which was published in 2001. In 2008 (or thereabouts), I met him at a dinner party organized by PopCon, and we talked on and on about Sister Rosetta Tharpe. In 2019, Cross proposed on Facebook that the City of Seattle buy Kurt Cobain’s former house on Lake Washington Boulevard—then on the market and asking for $7.5 million—demolish it, and transform the property into a park connected to the park with the bench that’s become a Cobain shrine. Indeed, it’s now called the Kurt Cobain Memorial Bench. Flowers, notes, loving graffiti are always to be found on and around it. People from around the world visit it. Some even experience something that can only be described as religious (“I tackled my midlife crisis by visiting Kurt Cobain’s Seattle shrine…“)

Sadly, our town had no time for such talk. City Hall is painfully pragmatic. The council is rarely guided by voices. Cross be damned. Cobain’s house, according to records, was sold during the not-long-enough lockdown for $7,050,000. It’s now another of Seattle’s many missed opportunities.

“It is possible for an owned thing to entirely lose its private value and become valuable only to the public,” I wrote in a Slog post that did all it could to support Cross’s proposal. “For example, could you imagine selling the actual Roman, wooden cross Jesus was nailed to? Could you imagine putting it on the market? And putting it into the home of one person? Something similar can be said of Cobain’s house. It is has a value for millions upon millions of humans whose lives are attached to the music and life of Kurt Cobain.”

What I failed to point out in that post was our city’s inability to name and raise to the heavens its worldly gods. Think only of the Museum of Pop Culture. The late city prince Paul Allen built it as a church for Jimi Hendrix, the subject of Charles Cross’s biography Room Full of Mirrors. It was designed by starachitect Frank Gehry to look like a guitar Hendrix lit on fire. But the neo-church thing never really worked out. The believers never showed up. Eventually reference to Hendrix, Experience Music Project, was watered down to the Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum, and finally “Experience” was entirely dropped, as was the bit about science fiction, for the current generic name.

The statue of Jimi Hendrix on Broadway is a joke. The cafe Starbucks devoted to the once-thriving jazz scene on Jackson was closed long ago and is still empty. It’s hard to believe that “a young Ray Charles had a regular gig at The Rocking Chair nightclub near 14th Avenue and East Yesler Way.” And let’s not get into Ernestine Anderson. Kurt Cobain, a god of the rock world, had no chance under conditions like this. He was lucky to get a bench. Our grunge dead have almost no shrines, memorials, Meccas. Why?

Flying into Memphis in 2017, I was stunned to see that the Mississippi delta did indeed shine “like a national guitar.” Paul Simon was right. He was going to Graceland. I was going to Graceland. But, as I later found, the whole city is devoted to its pop-music gods. Bar after bar, Beale Street (what Jackson failed to become), the Stax Museum of American Soul Music (what the Museum of Pop Culture failed to become)—Memphis displays at every opportunity its enthusiasm to deify the worldly. In fact, one of the biggest recent stories and controversies to come out of Memphis concerns Graceland. Poor Lisa Marie Presley died; she, of course, had debts; the house she left now belonged to the market. The city said no.

At the eleventh hour on a Tuesday in May, a Memphis, Tennessee, judge put a halt to the process that could have seen the famous estate of Elvis Presley auctioned off to the highest bidder. The whole episode was surreal and appeared to mark a sad postscript to the death of Lisa Marie Presley, the only child of the King of Rock and Roll, who died 16 months earlier.

Why do we, as a city, not feel this way about the house on Lake Washington Boulevard? Cross certainly did. Seattle did not. Unlike Memphis, we seem to lack this sense urgency or the understanding that certain parts of our culture are supernatural. It’s nearly impossible for us to spiritualize the material. We just can’t. How to explain this chilling lack? Maybe Gene Balk has the answer: “Seattle is the least-religious large metro in the U.S.” Is that what it comes down to? Toots & The Maytals’ call “to feel the spirit” is lost on us nonbelievers? The eyes of Wilbur’s Kurt Cobain’s looked angry to me.