Investors’ aversion to paying taxes is as strong as ever, and asset managers are expanding their toolkits to provide more solutions in separately managed accounts.

SMAs have one big advantage over tax-managed mutual funds and the inherently tax-efficient exchange-traded funds. In an SMA, the investor owns the underlying securities directly, so the tax management can be customized for the individual, which isn’t possible with a fund.

Assets in tax-managed SMAs have soared to more than USD 500 billion as of June 30, 2024, according to a Morningstar survey of leading providers. That’s a 67% increase from the end of 2022. For comparison, mutual funds that market themselves as tax-managed grew to about USD 73 billion, up from USD 60 billion, over the same period.

Direct indexing is still the most popular option for a tax-managed strategy, but firms have also been exploring other options—such as active equities and fixed income—to minimize capital gains taxes across a broader spectrum. As more financial advisors turn to model portfolios, there are options to help ease the tax burden of transitioning a portfolio and managing taxes on an ongoing basis.

You can find our full report on the growing number of tax-managed SMA options here.

Below, we’ll discuss firms’ different approaches to tax-managed strategies and the potential benefits and drawbacks.

Direct Indexing

Direct indexing has been used by high-net-worth investors for decades, but it has now become more widely available to retail investors. Innovations like fractional shares and advancements in trading technology have made it easier for asset managers to implement at scale.

The biggest driver of direct-indexing adoption is the tax-management component. Investing directly in an index’s underlying stocks through a separately managed account instead of a mutual fund or ETF tracking the same benchmark allows for individually tailored tax management.

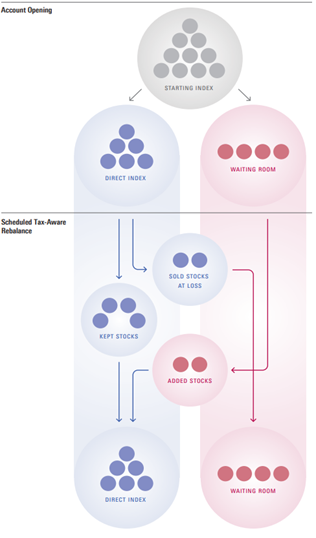

Direct-indexing providers will typically invest in a subset of stocks in the chosen index and sell those that have lost money since they were purchased to lock in the losses. They’ll replace those stocks with the leftover stocks in the index that have similar characteristics to stay fully invested. They can rebuy the stocks sold after 30 days to comply with the wash-sale rule that prevents people from taking advantage of tax-loss harvesting by buying something substantially similar immediately after locking in losses. Exhibit 2 shows how direct indexing could work in practice.

Active Equities

Though direct indexing isn’t going to lose its spot as the most popular tax-management option anytime soon, providers are working on expanding their capabilities to include options such as actively managed equity strategies.

Tax management has typically been a niche or specialty for a few active stock-pickers, but the biggest direct-indexing provider aims to make it more mainstream. Parametric announced in August 2024 that it was extending its tax overlay to active managers, and other tax-management providers like PGIM offer the services on their platforms. It’s only a matter of time until others follow suit.

One key difference in the tax management of an active strategy is how the tax losses are used. With direct indexing, the tax losses are typically used to offset capital gains from other strategies in the portfolio. The tax losses in an active strategy are first used to offset any capital gains the managers may incur from selling their winning picks.

Still, the tax management for active strategies isn’t as simple as it is with indexes.

For direct-indexing strategies, tax-loss harvesting is straightforward because there’s no preference for one stock over another if the overall portfolio has similar sector and factor exposures to the index. But for actively managed stock portfolios, investors are paying the managers to pick the best stocks in their universe. That creates a tension between harvesting losses and preserving the manager’s best ideas.

There are a couple of ways to tackle this problem. For example, if the manager owns a 10% position in Microsoft MSFT and it’s down 5% from when it was bought, the tax manager could sell it to lock in those losses and replace it with a technology sector ETF like iShares US Technology IYW. However, if the ETF has a positive return over the next 30 days, the portfolio manager can’t buy Microsoft because of the wash-sale rule, and there may not be a way to sell the ETF to buy back the stock without realizing capital gains. This could dilute the manager’s stock picks.

Parametric’s new option seeks to avoid that risk by taking a different approach. The active managers for whom it manages taxes will provide a list of substitute stocks to swap in as replacements. In the example above, that could mean replacing Microsoft with a tech stock like Broadcom AVGO (if that is on the manager’s list of next-best picks). This approach would work best with managers who have broadly diversified portfolios instead of those that are more concentrated.

Fixed-Income

Stocks aren’t the only asset class where tax management can be added to an SMA. However, investors using tax management for bond SMAs should damp their expectations for how much tax alpha they can expect from these portfolios. On average, tax-management providers we surveyed expect about half as much tax alpha opportunity from taxable-bond SMAs as they do equity SMAs.

There may be long stretches when there are few opportunities to harvest losses in bond SMAs. Bonds of the same credit quality and duration tend to move in tandem outside of idiosyncratic credit downgrades or defaults. This is even more so for municipal bonds that distribute tax-free income. That means tax-loss harvesting opportunities in bonds may be heavily dependent on when interest-rate and/or credit risk is out of favor.

From 2021 through 2023, the US Federal Reserve’s rapid hike of interest rates did present some tax-loss opportunities. In periods of rising interest rates, bond prices go down, and vice versa. In 2022, for example, the US 10-year Treasury yield rose to 3.88% from 1.63% at the start of the year, and the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index lost 13%. For most of the last half-century, though, interest rates have generally been falling instead of rising. In September 2024, the Fed cut interest rates for the first time since 2020, and it expects more cuts in the future. That could mean fewer tax-harvesting opportunities because of falling interest rates going forward.

Credit risk tends to correlate with stock market risk, so when there are large stock market selloffs, like in 2008 and 2020, bonds with a higher probability of default tend to get punished as investors seek safer havens.

But between such shock periods, bonds can be very sleepy, except for the occasional credit downgrade or default. That makes a bond a great diversification tool but a limited tax-management opportunity.

Model Portfolios

Advisors’ adoption of model portfolios is growing at a similarly blistering pace. Assets tracking model portfolios offered by asset managers grew by 50% to USD 450 billion over the two years ended June 30, 2024, according to the Morningstar Model Portfolio Landscape. If the home-office models of large wirehouses and broker/dealers are included, assets jump into the trillions.

Model portfolios are investment blueprints from asset managers or investment strategists. Most models can serve as the core of an investor’s portfolio and hold both stocks and bonds. Using a model instead of home-brewing their own portfolios allows advisors to spend more time on holistic financial planning and courting new clients.

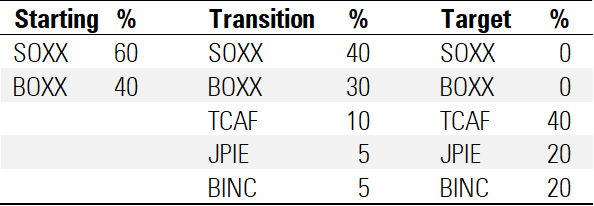

Taxes are one of the biggest hurdles that advisors face when moving clients to a model portfolio from other investments. Those clients are likely to have a decent amount of capital gains embedded in their existing portfolios and probably don’t want to pay big tax bills to move to models, even if they’re likely better long-term investments. Firms like J.P. Morgan’s 55ip have focused on using technology to make the transition between portfolios smoother by letting the advisor see potential tax hits and tailor how fast the client moves between portfolios. Like with direct indexing, it uses periods of market volatility to sell at a loss and then purchase the new funds. The exhibit below shows how a potential transition might look.

Once the transition is complete, ongoing tax management looks like other asset classes. The biggest difference is instead of swapping stocks or bonds, the model swaps ETFs for other ETFs, typically from an approved list of replacements. To avoid triggering the wash-sale rule, ETFs can’t have more than a 70% overlap of underlying investments.

Since a model portfolio will have fewer individual positions than strategies that invest directly in stocks and bonds, and diversified ETFs don’t have as much return dispersion, there may be fewer tax-loss harvesting opportunities for model portfolios over the long term.