The high-cost environment in commercial real estate has primarily been driven by the Federal Reserve’s current tightening cycle. Rising borrowing costs have dominated industry discussions, and investors are waiting with bated breath for when interest rates finally fall. However, interest rates aren’t the only rates that property owners pay close attention to. In recent years, property insurance rates have skyrocketed, increasing operating expenses and putting significant downward pressure on net operating income.

The Deloitte Center for Financial Services predicts a substantial rise in commercial property insurance costs across the U.S., projecting an increase of nearly 80 percent by 2030. This means average monthly premiums for commercial properties are expected to soar from $2,726 to $4,890. Between 2013 and 2023, these costs almost doubled as insurers strive to keep pace with escalating losses.

The main reason for these soaring rates is extreme weather. In 2023, there were a record-high 28 separate billion-dollar extreme weather events, with estimated recovery costs totaling $92.9 billion. These events included 19 severe storms, four floods, and two tropical cyclones. Billion-dollar extreme weather events increased by 56 percent last year compared to 2022, and they were up 180 percent compared to a decade ago.

Rising insurance rates significantly impact commercial real estate owners. According to MSCI’s U.S. Quarterly Property Index, insurance costs as a percentage of income receivable have more than doubled, jumping from 1 percent to 2.3 percent between 2018 and 2023. States like Florida and California are feeling the brunt of this increase. In the third quarter of 2023, these states recorded the highest insurance costs as a percentage of income receivable, with Florida at 4.4 percent and California at 3.6 percent.

Record-breaking insurance rate hikes can add hundreds or even thousands of dollars to annual costs, depending on the building’s size and location. In some cases, soaring premiums erase an entire year’s profits for building owners. The surge in insurance costs is also reported as one factor in the recent decline in property sales. “Deals that may have just fit what we are buying are now off the table because the insurance costs are just too high,” said Ian Bel, managing member of multifamily landlord Olive Tree Holdings.

Mortgage lenders usually require property owners to obtain insurance covering the total rebuilding cost after a natural disaster. Some owners are trying to lower the amount, saying it’s unlikely an entire building will be decimated. Insurance brokers say some banks are open to the idea, especially if the rising costs threaten a default. Other banks are still insisting on full coverage.

The recent case of Three Pillars Capital Group offers an illuminating example. Until May 2023, real estate owner Three Pillars paid over $630,000 annually to insure Houston’s 544-unit Del Mar Apartments complex. When the insurance expired and Three Pillars requested quotes for a new policy, the estimated cost tripled to about $1.8 million. Three Pillars tried to persuade its mortgage lender to agree to lower coverage. Instead, the lender forced it to accept a new insurance policy that cost nearly $2.3 million annually.

Due to increased insurance payments, Three Pillars claimed the building’s revenues were no longer enough to cover expenses and debt payments. Three Pillars recently took the unusual step of suing its lender for breach of contract and fiduciary duty. They alleged their mortgage lender forced them to obtain unnecessary and costly insurance.

Gambling on the future

Unusual lawsuits like Three Pillars are one effect of a property insurance market buckling under the weight of climate change. Property owners are devising creative solutions to deal with the problem, and one of the more unique ideas is self-insurance. On the surface, the idea seems like a desperate and wild choice. However, in states like Florida, where reforms have not slowed the insurance crisis, more building owners are open to self-insurance as an option.

Self-insurance is when a property owner pays all or part of their own insurance losses and assumes the role of an insurer by establishing internal systems to settle their claims. Also referred to as ‘alternative risk transfer,’ property owners design their own insurance program with self-insurance.

The benefits of self-insurance include securing broader or more appropriate insurance coverage that may not be available commercially. Self-insurance may also create an incentive to make buildings more resilient to natural disasters because, if managed properly, they can reduce premiums.

Self-insurers adopt formal systems for paying losses, and the function is sometimes outsourced to a claims manager or third-party administrator. Self-insurance requires a more hands-on approach to loss prevention than if a property owner were insured in the traditional market. It also provides a greater incentive to reduce claims, save premiums, and increase profits and cash flow.

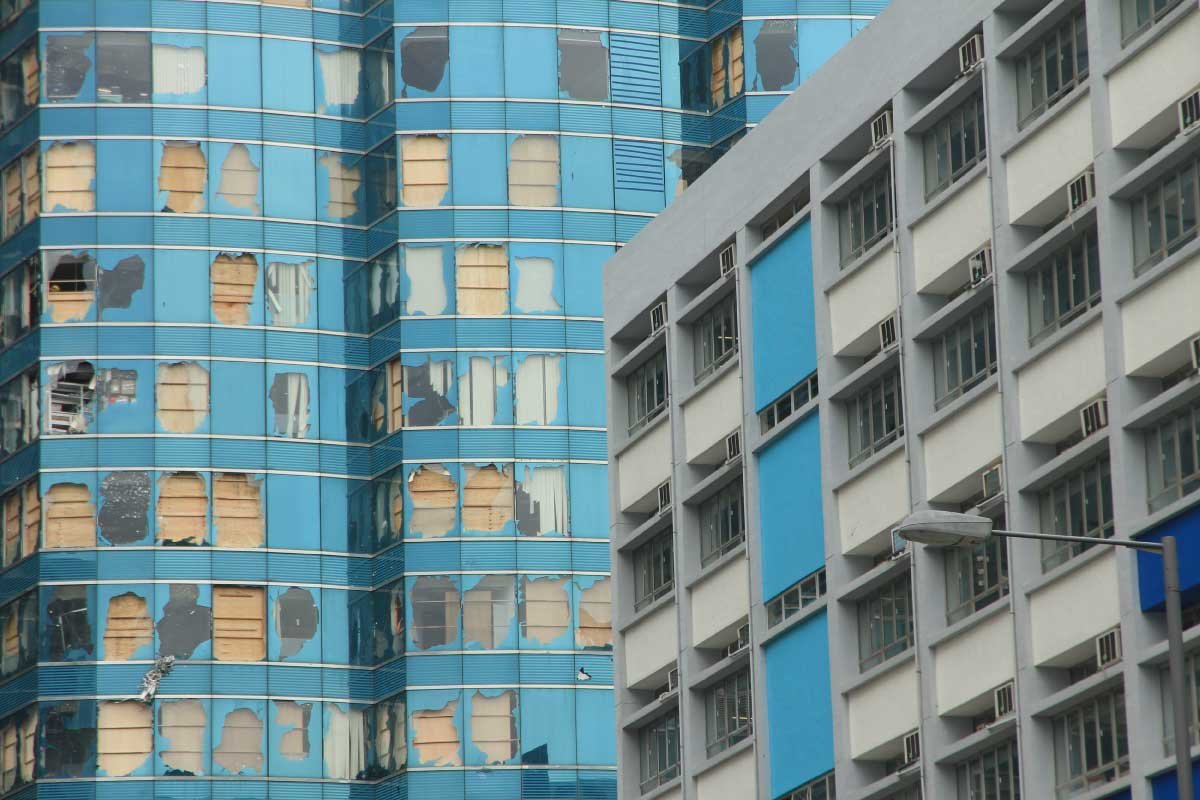

While self-insurance offers numerous benefits, it also carries substantial risks. In a severe natural disaster like Hurricane Ian that struck Florida in 2022, some property owners might find the enormous costs of clean-up and rebuilding unaffordable. This scenario could spell disaster for the property owners and tenants, whose belongings and livelihoods could be completely devastated.

Mortgage companies typically mandate that borrowers maintain traditional insurance policies. Similarly, some vendor contracts require traditional insurance to safeguard goods stored on-site. However, self-insurance can be an appealing alternative for property owners not bound by these requirements, especially in markets like Florida, where insurance rates are soaring and qualification demands are becoming more stringent.

In many cases, self-insurance is an option that works best with larger real estate companies. A real estate firm with dozens of properties may have the financial wherewithal to withstand a natural disaster. Self-insurance would be an economic calculation to a larger firm and a gamble that if the worst does come to pass, they have the capital required to ride out business closures, rebuild, or sell the land.

A smaller investor with a handful of properties is in a much different position. Investors like that are more likely to be unable to survive the financial shock from a major hurricane, especially if their building is destroyed and they lose the tenants they depend on for revenue. The ultimate solution is for state policy to reign in insurance costs, which has proven to be a complicated problem.

In Florida, reforms in the past two legislative sessions and a special session last year have aimed to reduce the number of lawsuits blamed for many of the state’s insurance issues. For the most part, the impact of the reforms hasn’t been felt yet. Many insurance carriers continue to stop writing policies in Florida because they fear the increasing strength of hurricanes. Meanwhile, the carriers staying in the Sunshine State continue to raise rates significantly.

These factors have left many property owners, big and small, desperate enough to consider a solution like self-insurance. The reward for self-insurance is not riches but survival, which means some property owners are willing to gamble their future on the idea, even if it turns out poorly.

Less drastic solutions

Of course, self-insurance is not the only option. Several other strategies for reducing property insurance costs aren’t as drastic. The number one strategy may be a basic reality check: premiums will keep increasing, and bottom lines must be adjusted to account for this. Insurance is no longer just another expense item rolled over annually, and building owners may have to get used to more frequently changing packages and budgeting more for insurance for the foreseeable future.

Closer relationships with contacts at carriers may also be needed. Property owners can contact insurers as many as 180 days before applications are due rather than the typical 90 days. They may also provide more detailed supporting data on reducing risk and limiting losses. Application submissions have taken on increased importance, and more than ever, they need top-notch narratives of loss-control strategies.

Property owners in disaster-prone areas may also consider alternatives to traditional commercial property insurance, such as ‘parametric insurance.’ This type of policy pays out a set dollar amount based on the characteristics of a natural disaster instead of the repair costs. The ratio of loss to payout is typically less favorable with a parametric policy than a traditional one, but it can give building owners more stability.

Some property owners are considering self-insurance, highlighting how challenging the commercial insurance market has become for the industry. Extreme weather may not slow down soon, but the market for commercial property insurance may eventually stabilize. Higher premiums could attract fresh capital for the insurance industry, as some view them as an entrepreneurial opportunity ripe for innovation. For now, property owners are feeling the brunt of higher insurance costs at a time when borrowing costs are already high. Self-insurance is a gamble some building owners are willing to take in an insurance game that’s becoming very high stakes.